I doubt the English poet and novelist Horace Smith is well-known to readers. His most famous work was the Rejected Addresses, parodies of the leading poets of his day, co-written with his brother in 1812. What brought him to my attention, however, was the friendly competition between him and Percy Bysshe Shelley in the winter of 1817-18 that produced two poems called “Ozymandias.” His is the contextual footnote of the two, but the one which is most direct about our civilisation’s own mortality.

I recommend reading the poem in question first, as well as Shelley’s “Ozymandias” and my defence of it, since this piece shall only note what appears pertinent to avoid extensive repetition. After all, this is only an incidental addendum to the previous piece.

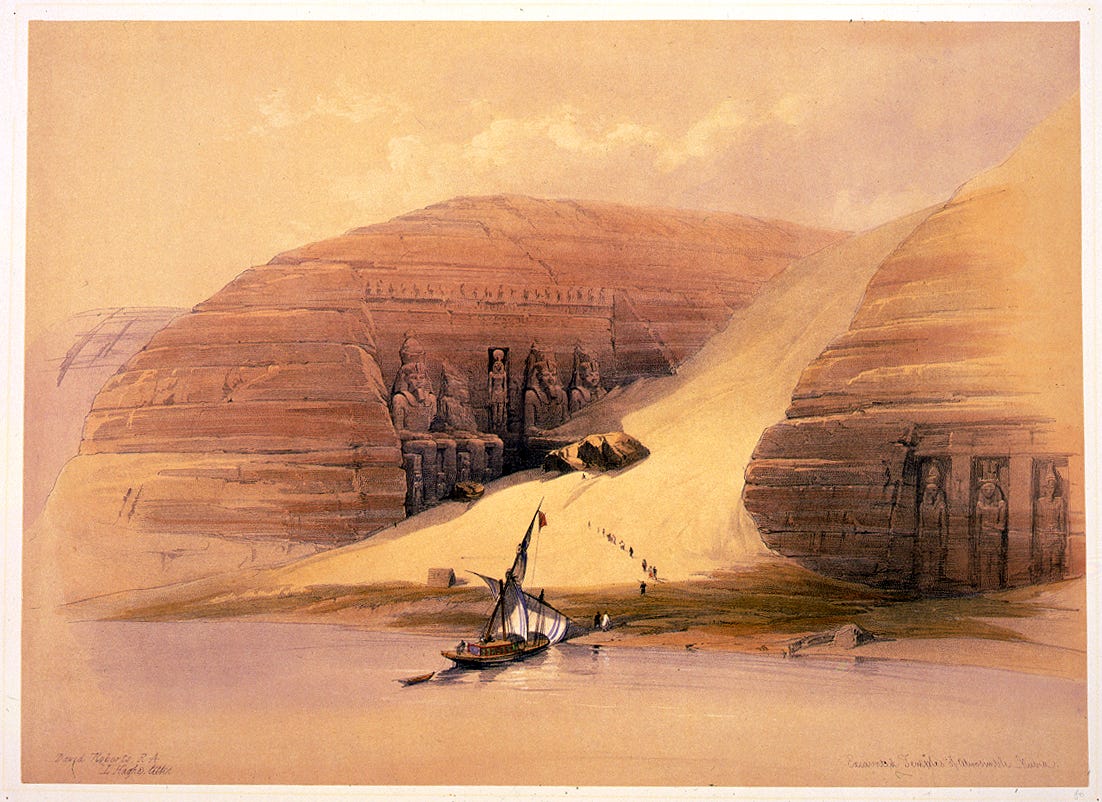

What one observes in Smith’s poem is three cities and civilisations being equated with one another: the lost Egyptian city containing the statue of Ozymandias, Babylon and London. The Egyptian site, according to the description given by Diodorus Siculus in the passage which spurred both “Ozymandias” poems, was the Ramesseum mortuary temple near Thebes. The actual capital built for Ramesses II, Pi-Ramesses, was not rediscovered until the 1960s, whilst the replacement which reused most of its building materials at Tanis had no large-scale excavations until the 1860s. Regardless of the poetic licence used to emphasise the colossal statue amidst the desert sands, the ruin of the Ramesseum remains a great source of wonderment after more than 3000 years of existence.

Babylon, meanwhile, is timelessly iconic. It was one of the centres, if not the sole centre, of the ancient world for well over a thousand years. It was canonically immortalised in the Bible, let alone the writings of numerous classical historians and paintings of biblical tales or Alexander’s conquest. Babylon was not forgotten, but it was certainly lost more than a thousand years before Smith wrote his poem. Apparently, Europeans could not consistently find Bablyon until the eighteenth century and excavations for relics had only started taking place a few years before Smith compared the city to the Ramesseum. It is debatable which set of ruins was in better condition or more visible in the late 1810s.

As for London, it yet exists and somewhat in the shape Smith would have known. Although the Blitz, the planners and the skyscraping modernisers have each damaged the fabric of the venerable centre, its cornerstones are recognisable down the centuries. They are the same as Babylon and Thebes: temples, palaces, fortresses, the architecture of governance. Despite the technological advancement of this civilisation, it is as mortal as all which preceded it. In this respect, the essential meaning of Smith’s “Ozymandias” is starker than Shelley’s and a warning to the present age. Whilst our hubris is not the same as that attributed to Ozymandias, it is a potentially fatal condition nonetheless. The sum of fears of being forgotten in contemporary society are doggedly misplaced towards presentist and petty concerns, indeed those which may stand to be easiest disposed by posterity. Smith does not offer an answer for avoiding the fate of Ozymandias’s realm, for there is no ultimate remedy to the fate of cities or civilisations, but the least a responsible custodian of civilisation should glean are those solutions which our inheritance proves are patently incorrect.