This is the second defence of particular Romantic poems I promised in my prior discussion of William Blake’s “London.” I strongly recommend reading my previous piece before this one, or at least its first two paragraphs, as that introduction equally prefaces these thoughts about Percy Bysshe Shelley’s “Ozymandias.”

As one of Shelley’s best-remembered poems, much ink has been spilt over who or what he was attacking or really saying. The wisdom of this interpretative approach has its limits, since one can appreciate it just as easily for its exploration of immemorial aspects of human nature and time. The more valuable use of this digital ink, these pixels, would be to observe the poem’s most straightforward context and from that vantage respect the succinct capturing of themes by Shelley.

The best place to start with “Ozymandias” is Ramesses II, who was known as Ozymandias to the ancient Greeks. He was a tremendously successful pharaoh and built so the Egyptian kingdom would know his might, even long after his death. The epitome of his building projects was the colossal statues of his image, one of which was slowly making its way to London and the British Museum at the time Shelley composed his poem. In the first century BC, some thousand years after Ramesses’s death, Greek historian Diodorus Siculus’s Bibliotheca historica quoted an inscription on one of these statues of the pharaoh goading onlookers to outdo his work. It was this passage that acted as the prompt for Shelley and fellow poet Horace Smith to write competing sonnets in the period around Christmas in 1817/18. Smith’s “Ozymandias,” not to be confused with the present subject, might be worth its own brief piece in the future for its very explicit warning to modernity.

Even with this quite matter-of-fact context alone, Shelley’s “Ozymandias” still works. Ramesses was not worshipped as a worldly deity eternally: his purpose-built capital was abandoned after about 150 years, whilst his temples slowly became disused and forgotten by time over the course of Antiquity. The first successor to evoke his name, Ramesses III, was also a great pharaoh for defeating the Sea Peoples during the Bronze Age Collapse, but heralded the terminal decline of the New Kingdom. His successors were also called Ramesses, but their control became successively weaker until one half of the Egypt of Ramesses XI was de facto ruled by the priesthood and the other half was governed by the future initiator of the Third Intermediate Period. The simple and undeniably true message of the poem is that nothing lasts forever. The rise of someone or something predicts a fall. Temporal entropy will eventually erode everything which seems solid at a point in time.

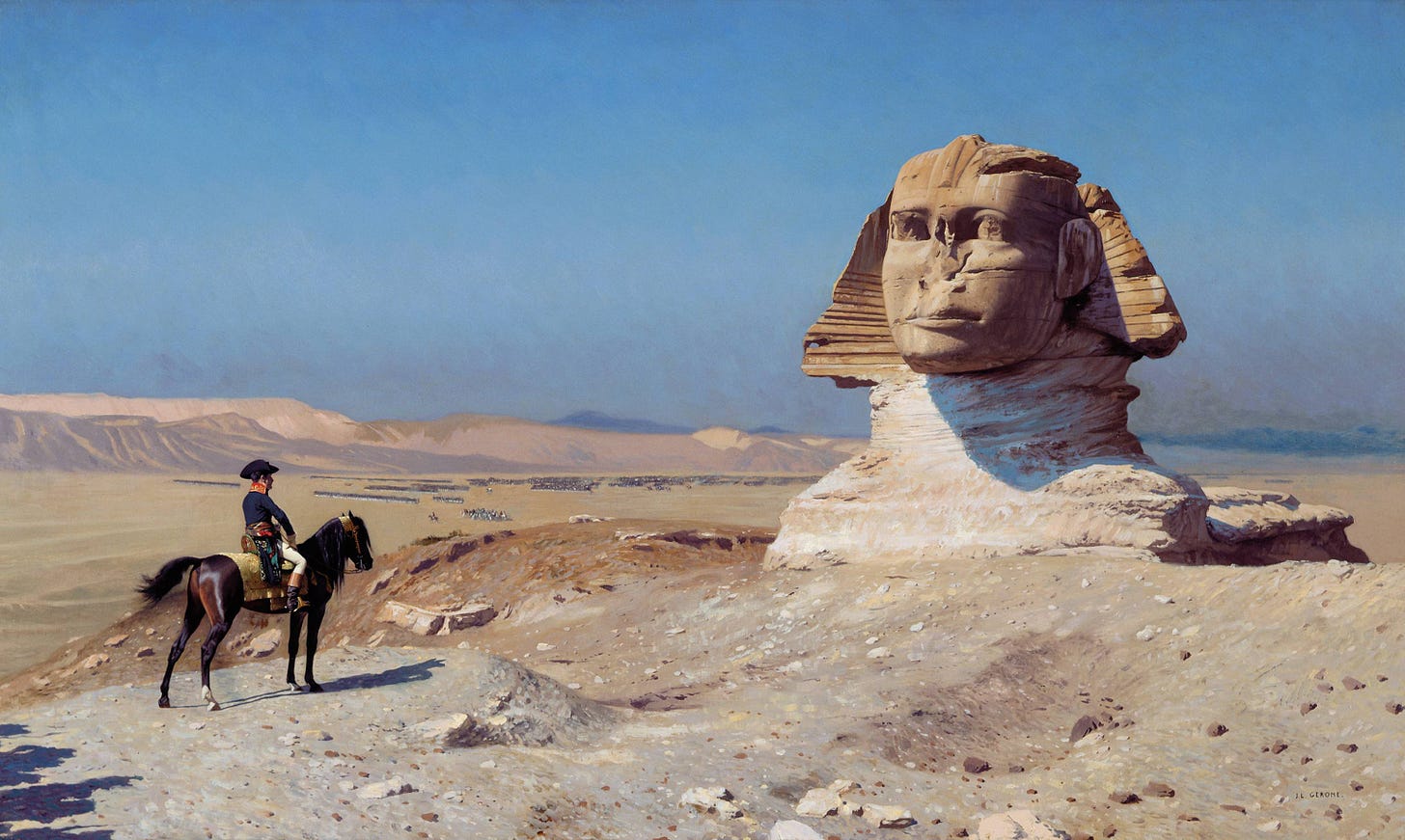

However, the fact that the physical remnant is not entirely lost, both in the poem and reality, grants it a certain afterglow in the imagination. Between this recognisably Romantic impulse and a somewhat more scientific curiosity, Europeans had begun to rediscover the ruins since Napoleon’s expedition of 1798-1801. The “two vast and trunkless legs of stone” amidst the “lone and level sands” is an instantly evocative image, illuminating the appeal of the contemporary wonder with the unknown. In one sense, the reclamation of the “colossal wreck” from oblivion and its fortification in the mind allow Ozymandias a renewed claim to permanence in history, rather than as an enduring object of the present, so long as the triumphant historian avoids befalling the same fate. The poem does not reach the extent of worshipping the ruins, as the character of Ozymandias is rendered colder than Diodorus’s already hubristic inscription. Yet, it almost doubtlessly reflects how the burgeoning field of Egyptology could make an impression on Romanticism’s melancholic longing for an obscure idyll in the past. After all, no matter whence these ruins arose, they have acquired a silent tranquillity in the desert.

“Ozymandias” is an effective parable about tyranny or empires, of course, but its historical allegory applies the poem to the level of civilisations and throughout time. Minds are animated by these monuments, now memorials, to ambitions most today can scarcely comprehend. They are provoked further by the inkling of fear about what exactly can ensure civilisational immortality if the pyramids or other colossal structures were not enough. Some of the ancients’ ruins may have been edifices to hubris and folly, but these qualities are innate to human nature. Where is the Tower of Babel now? What is our Tower of Babel? These questions gnaw at every civilisation’s condition, as Death lurks in the shadows.

“The young Corsican, seated on his horse, is gazing in meditation upon the enormous enigmatic face of stone, that strange memorial of titanic ambitions, of forgotten sovereigns, of a vanished race. ... The master has kept out all distracting details; even those I have mentioned are felt rather than observed, not even the Pyramids are shown – only the cloudless sky, the smooth sand, from whose drifts the gigantic visage rears itself and the solitary, self-communing man.”

- The New York Times commenting on Bonaparte Before the Sphinx, presented under the title Oedipus, at the Paris Salon of 1886.