The Grumbling Times Supplement - Summer/Autumn 2024

Thoughts on mythology, deindustrialisation, constitutional reform and much more, if much delayed.

Surprisingly, this series has not been completely forgotten by this writer. As quite a few months have passed since the last instalment of references and notes, there is naturally a varied collection of ideas to delve into. Going forward, given the erratic frequency of writing published elsewhere, this series will remain as irregular as previously implied by its long absence.

On the Disappearance of British Mythology

Permanently out of print1 at an erstwhile publisher, with whom one has lacked any interest in remotely associating oneself for some months due to their escalating radicalism and corresponding marginalisation of temperate opinions. They are only deserving of contempt now.

Some possibly self-indulgent words on this matter. The world today, whilst still good at its core, is beset by much madness. Bitterness and resentment mercilessly rot intellects. Nihilism pervades and annihilates many others. Sanity is left by the wayside as spiralling into absurdity is incentivised. Mutual senses of compassion, empathy, dignity and respect, vital for any community to exist, are slowly seeping away. Political radicalism in these times, no matter its social or political origins, must never succeed in its stooping to and encouragement of the most negative sentiments and impulses of the age. Perpetrating a wrong against different wrongs will not set anything right. Only in rising above the seething maelstrom and reclaiming each’s individual humanity from the digital ratchets which might destroy it can good people begin to address the many challenges of the present. This Substack remains one modest attempt amongst many to find a path forward which is necessarily decent, intelligent, moderated, prudent and flexible. Conservatism, although imperfect as all ideologies or philosophies are, is the closest amongst contemporary sets of ideas to encompassing all that is needed, whilst being more averse to needlessly repudiating past institutions, traditions and knowledge that may yet prove useful again. Though some of my writing might foray into other subjects, such as the notes below, this overall focus will continue to shape my choices in a hopefully positive and constructive direction.

Bibliography

Ashe, Geoffrey. Mythology of the British Isles. London: Guild Publishing, 1990.

Scruton, Roger. Modern Culture. London: Bloomsbury, 2018.

Tolkien, J. R. R. The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays. London: HarperCollins, 2006.

Notes

This article concerned the erosion of the rather expansive repertoire of British mythology from popular memory. From the popular twentieth-century children’s history book Our Island Story, it can be inferred that some of this decline was a relatively recent process, although the frequently criticised phenomenon of deconstruction in academia is likely too novel to serve as an adequate explanation. However, the discrediting of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia regum Britanniae as a legitimate history (for it certainly was not) during the early modern period left little of the mythological inheritance that could be sincerely believed, which in turn made its sapping from popular memory quite terminal. It is simply a fact of life in an enlightened society that the development of the mythological corpus is frozen, aside from the occasional cultural work, and ceases to actively influence a more rationally inclined population (not that its sway was ever total to begin with, unless religion is regarded as its own sort of mythology). Despite the challenges this poses to conserving mythology from being entirely forgotten, the general evolution of society that reflects certainly remains positive.

In the present, British mythology ought to be seen as an important facet of the nation’s cultural history, as well as one element (of indeterminate, albeit not critical, importance) of the tacit traditions, customs and habits that bind society together. It may also still act as a wellspring for new cultural works if not forgotten, a noteworthy example being the literature of Tolkien. In this light, it should be conserved as part of the duties of Edmund Burke’s eternal trusteeship, from which progressive cultural attitudes have sought an ill-advised liberation in recent decades. On the other hand, contorting aspects of myths into kitsch or nostalgias will not be effective. After all, being nostalgic for what are essentially fragmentary and fictional realities evidently makes no sense. Even worse would be to attempt to force mythology into the basis of a nationalism or nationhood of some twisted sort, not only an inherently abhorrent idea (as nationalism invariably produces undesirable results) but so deeply inauthentic to reality that it would inevitably shatter upon conception.

A possible avenue for parts of British mythology to receive greater recognition and attention is the concept of historicity, the study of the veracity of historical claims. As conjectured by Tolkien and observed by Ashe, some aspects of British mythology can demonstrate a surprising proximity to modern interpretations of the island’s early history. Subjecting myths to this sort of rigorous academic study forces the entire history of their development on show, as well as their subsequent influence on significant works of culture. Overall, there is a cultural history or tradition to explore here, in a similar manner to how classical mythologies have long been interrogated. Indeed, Ashe argues such a sober and analytical approach to the mythological corpus reveals a cohesiveness similar to the Greeks, despite the fragmentary evidence modern historians possess.2 This method obviously will not return mythology to living culture, which for the reasons mentioned above cannot be the aim, instead to a greater historical awareness as historians should strive towards for history generally. Even if the evolution of mythology is ‘dead’, conserving knowledge of this facet of cultural history is preferable to letting it slip away altogether.

There is a notion that knowledge of mythology and other aspects of cultural heritage have somehow been ‘taken’ by some undefined higher authority, but this is very reductive and a product of mass apathy. Knowledge of mythology has always been irrelevant for enabling normal participation in society, the basic objective of state education. The same is true of all but a minimal level of history teaching, which is more regretful given the ignorance that can foster in adulthood. There is then the question of where mythology could be placed in the curriculum. It cannot be history as its stories are effectively fiction; if treated as literature, it should not dominate the already diverse and crowded range of works rightly taught (including products of itself, such as some of Shakespeare’s plays). In actuality, the ideally thoughtful manner of discussing the topic above, exploring the nuances of an aspect of cultural history with a slight view towards conservation, is best suited to an undergraduate level of study. It is also a fact that nobody can compel an individual to learn privately subjects, such as history, which might give them some grounding in an otherwise restless world; forcing this upon somebody would simply breed resentment. That people in recent decades seem less willing to pursue intellectual interests through reading can easily be connected to the well-documented decline in reading books for pleasure and books of an extended length. It is beyond one’s expertise to suggest how these trends might be abated or reversed.

The Death of Britannia Agoraia

Available via The Critic website.

Bibliography

Burja, Samo. Great Founder Theory. USA: 2020.

Ruskin, John. Traffic. London: Penguin, 2015. Contents first published over the course of the 1860s.

Notes

Since this article was published, British deindustrialisation has continued apace, lately from the suspension of steelmaking at Port Talbot and shipbuilders Harland & Wolff entering administration. The care expressed by the present government about the loss of thousands of good jobs and vital national capabilities remains, similarly to its predecessor, inadequate. Previous commitments to state infrastructure investment are under substantial scrutiny by the bureaucracy, whilst political capital in energy policy has been again misallocated to means which cannot guarantee consistent energy abundance (one of Britain’s starkest disadvantages as a potential location for new industry). At the same time, both the threats to globalisation (including from geopolitical allies like the United States, where there is substantial interest for more protectionist measures) and our reliance upon it are equally unchanged.

Amongst proponents of reindustrialisation, having such a process led by the market over the state is currently a minority viewpoint. It is a shame the experiences of nationalised industries under the governments of Clement Attlee, Harold Wilson and James Callaghan are being forgotten or ignored in debates on the topic. It is simply not the place of government to directly manage steelworks or carmakers. After an initial period of focus, newly rebuilt industries under the state would have every chance of falling into the same patterns of long-term neglect as before. Successive governments, even at times of state largesse, have proved generally unwilling to burden the taxpayer with the risk of substantial capital investment to promote innovation and competitiveness with other markets. Elsewise, these corporations would again become steadily sclerotic as tools for regional redistribution. Unfortunately, similar trends in state infrastructure can be observed on both counts, constituting another major block to substantial economic growth in the private sector (ergo government tax revenues) and increasing overall living standards. Furthermore, foreign investor guidance may prove absolutely necessary to restore the pools of tacit and proprietary knowledge in industries ravaged by deindustrialisation.3 At a certain point, expanding industries might be able to rely more on domestic talent to innovate and establish competitive advantages over other economies, but this process is still firmly the domain of the private sector. As stressed in the article, the role of government in reindustrialisation is to improve the tax, regulatory and energy policy environments in order to encourage, rather than ward off, investment in new manufacturing. If state actors want to keep a characteristically high opinion of themselves, it might be argued these actions, alongside a decentralisation of power from government over industrial strategy, bureaucratic control of infrastructure projects and so on, are the prerequisites to reinvigorating private sector investment into important industries.

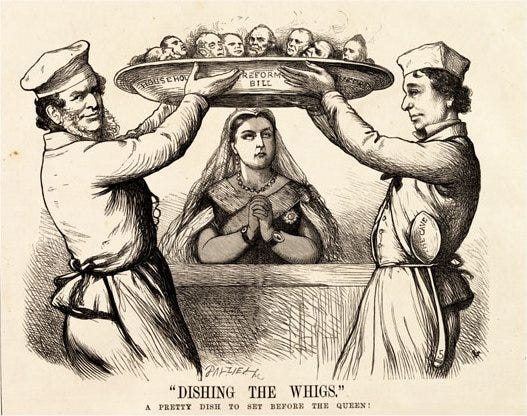

“Dishing the Whigs:” A Strategy for Opposition?

Available via the ConservativeHome website, albeit under their own title.

One more personal note regarding publishers. My only regret with ConservativeHome is not working with them sooner. They are an exemplary conservative publisher: receptive towards the Conservative Party, but not beholden to it; tolerant of diverse opinions from writers, but only if they are both sane and grounded in constructive conservative politics. This association has been nothing but rewarding so far, hence readers should expect further articles with them in the coming months.

Bibliography

Himmelfarb, Gertrude. “The Politics of Democracy: The English Reform Act of 1867.” Journal of British Studies 6, no. 1 (1966): 97-138.

Kirk, Russell. Concise Guide to Conservatism. NJ: Regnery, 2019. First published 1957 by The Devin-Adair Company.

Saunders, Robert. “The Politics of Reform and the Making of the Second Reform Act, 1848-1867.” The Historical Journal 50, no. 3 (2007): 571-591.

Notes

The following paragraph is a new note, offering some further reflections on the topic in November 2024, alongside the addition of the Saunders source above. A more concise interpretation, to the best of one’s ability, of why the Second Reform Act passed might be of benefit to readers. Specifically, why did Conservatives change their minds on reform in 1867 and Liberals keep voting down their own bills until they lost control of the issue? Political opportunism, from Disraeli, Derby and the Conservative Party at large, was doubtlessly crucial, although the Act did concur with the conservative approach to change. This explains what would be an otherwise impossible reversal in opinion on reform between 1866 and 1867, and was clearly responsible for the fall of Russell’s government (since the Adullamites certainly were not voting to put their own party out of power). The Act was also a compelling chance for Disraeli to spite his main rival Gladstone. Going further back, as covered by Saunders, Derby and Disraeli’s previous minority ministry of 1858-59 equally grasped their opportunity to create a more pro-Conservative electoral landscape, but the bill fell like others of the era from opposition to the effects of certain intricacies. The bulk of Liberals remained caught up in this capricious thinking until and even during the 1867 debates, driven by a belief in liberal individualism, Benthamite utilitarianism and fears about working class domination over more ‘cultivated’ “advanced liberal” groups. Meanwhile, the Conservatives just wanted a reform bill of their own creation that would not keep them out of office for another generation. Flooding Liberal-leaning boroughs with new voters, through simple household suffrage, hence did not trouble most Conservatives much. If Disraeli’s germinating one-nation conservatism was correct about the working class, then all the better. The extent to which the enigmatic Disraeli’s own ideas influenced proceedings, especially in accepting compound householder enfranchisement without consultation and despite prior backbencher opposition, was and remains unquantifiable but certainly not discountable. However, what this moment in political history surely contributed to was the growing mythos around the future Prime Minister.

It has proved overly optimistic to suggest Labour would abide by most of their election manifesto promises. However, this does not completely invalidate the idea that the Conservatives should endorse and seek to further more worthwhile government proposals. The two policy areas named in the article, planning and NHS reform, remain relatively close to the consensus position of the final Conservative leadership candidates at the time of writing.

If the Liberals had succeeded with their Reform Bill in 1866, it likely would not have settled that aspect of the constitution as long as Gladstone or Russell anticipated. The Radicals and Disraeli alike would have continued advocating for more extensive reforms. Prevailing trends in social reform and education, the latter of which the Liberal Party certainly supported as a means to prepare the ‘artisans’ as a (pro-Liberal) voting demographic, would have eventually produced a popular appeal for mass politics. Whether a growing Reform League, the Radical organisation campaigning for household suffrage in the mid-1860s, could have enjoyed more success in this scenario than their Chartist predecessors is uncertain. Either way, household suffrage would have likely been a reality by the 1880s, during which (returning to the actual timeline of events) there was ample evidence both parties finally settled into and became comfortable with the paradigm shift to mass politics Disraeli masterfully triggered in 1867.4

The basis of one-nation conservatism ought to be explored further, both in reference to the article and more generally amongst contemporary conservatives. The cross-class alliance Disraeli aspired towards is technically still extant, the position of the landed aristocracy being replaced by a plainer social/political elite composed of those occupying positions of political and/or thought leadership within the Conservative Party. This switch occurred in around 1920, or else through the leadership of Bonar Law, as the socially and economically declining aristocracy abandoned attempts to repeal their political curtailment in the Parliament Act 1911. In the absence of practised conservative philosophy within the party recently, the outlook and standards of one-nation conservatism have been solely decided by the consensus opinion of party leaders. Rifts in opinion between the classes were obviously possible before this point, as signified by election losses, but the specific pattern of alignment and disconnect under the label during this century has brought forth much worse consequences for the party. Despite all that has transpired, the idea of one-nation conservatism remains eminently desirable, but with a re-solidified foundation in consistent principles and conservative ideas.

The article’s mention of a “repository of wisdom” in the past is a reference to Kirk’s Concise Guide to Conservatism, specifically the first chapter outlining the essence of conservatism. This book cannot be recommended enough, not only as an accessible introduction to the Anglo-American conservative tradition, but as a work which can be revisited periodically to remind oneself of its roots. It seems a healthy task, for those who want more than a passing engagement with the philosophy, to ground oneself by consulting sweeping surveys like Kirk’s every once in a while, to admit and rectify errors of thought acquired from poorer tendencies. Additionally, one might be able to attain the prudent self-improvement Kirk would endorse to most effectively, in his words, “resist the levelling and destructive impulse of fanatic revolutionaries.”5

The Threatened Independence of the Lords

Available via the ConservativeHome website, albeit under their own title.

Bibliography

Bagehot, Walter. The English Constitution. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009. First published 1867.

Pakenham, Francis. A History of the House of Lords. Stroud: Sutton Publishing, 1999.

All other references to reported facts and certain data regarding the Lords can be found through their respective hyperlinks in the article.

Notes

Within Parliament, strong defences of the present constitutional arrangements have been mounted by Lords Frost, Moore, Forsyth and Roberts (all life peers), the perhaps more biased 2nd Baron Strathclyde and 19th Earl of Devon (both sitting hereditary peers), as well as MP Andrew Rosindell in the Commons. These are all recommended reading/listening, with several touching upon similar arguments to those made in the article.

The Lords named include some from the Crossbench and the non-affiliated, the collateral damage to which from Labour’s schemes must not be ignored. Bear in mind that their numbers have never recovered from the House of Lords Act 1999. Conservative peers forcing the creation of the House of Lords Appointments Commission and ‘people’s peers’ largely failed at restraining prime ministerial patronage or preserving unchanged the most obvious manifestation of the House’s independence. Lord Longford’s History records there were 322 on the Crossbench alone on 1st December 1998, but now there are just 184 alongside 43 non-affiliates. 35 hereditary peers (33 and two respectively) stand to be removed from these ranks, and what was once a strong independent bloc betwixt the parties that could even challenge the massive Conservative peerage of old will be condemned to a rather distant third place.

A less honourable mention ought to go to Sir Gavin Williamson, who is attempting to garner cross-party support in the Commons for an amendment to abolish the Lords Spiritual outright. He has clearly not received Benjamin Disraeli’s memo that the first duty of a Conservative is to maintain the constitution. Should this amendment get somewhere, which is unlikely due to the conspicuous absence of the bishops in Labour’s plans for Lords reform, it might prove impractical to implement without abolishing the House altogether. Given the centrality of the Lords Spiritual to the House of Lords, as the other ‘half’ to the Lords Temporal, the amendment may encounter the limits of the traditional constitution’s flexibility, akin to Labour’s failed attempt to abolish the Lord Chancellor in what became the Constitutional Reform Act 2005. If this is some sort of Machiavellian manoeuvre, expelling a steadily more progressive grouping under the guise of furthering modernisation to get revenge at Labour’s politically targeted removals, it is just as foolish. Not only should political battles not be fought by torching parts of the constitution to the rival party’s disadvantage, removing the bishops would destroy another group that is independent of party political patronage. It would only compound the ramifications of removing the hereditary peers for future governments (Conservative or otherwise) discussed in the article and by other commentators, not ameliorate them.

Whilst on the subject of constitutionally significant positions, the disentitlement of Earl Marshal and Lord Great Chamberlain to seats in the Lords will create some novel and problematic constitutional questions once Labour’s House of Lords Bill becomes law. The removal of the latter, who serves as the King’s representative in Parliament, is particularly worrying. Will every holder of both titles be granted a life peerage to ensure all ceremonial functions proceed uninterrupted, or will this government be harsher than Tony Blair’s by simply ignoring them? If the latter, a measure of improvisation and pretending things remain unchanged may work in the short-term, but this would be a tenuous state of affairs. In his speech to the Commons during the Bill’s Second Reading, Rosindell was wise to stress how the hereditary monarchy will be undermined by delegitimising the same principle of succession in the Lords. Providing no reprieve for the previously mentioned royal functionaries will just aggravate this effect.

If there is sufficient interest from readers in the summary contained within this section’s notes, I will consider releasing the article on this Substack.

That is not to say the sources for Greek mythology are complete, since the vast majority of ancient Greek works have also long been lost. I recommend Samo Burja’s articles/lectures on ‘intellectual dark matter’ for more on this point and its implications.

Again, see Burja’s extensive work on knowledge.

Perhaps, in the alternate timeline suggested, Gladstone would have eventually found the courage to bring about mass politics himself. We shall never know.

American spelling of ‘levelling’ altered to personal taste.