The story of the construction of Marble Arch (or should it be the Marble Arch?) is well worth recounting. One reason for this is its obscurity in historical memory. More importantly, it holds as an example of propagating beauty and high art through sculpture despite the chance for entropy to take its course.

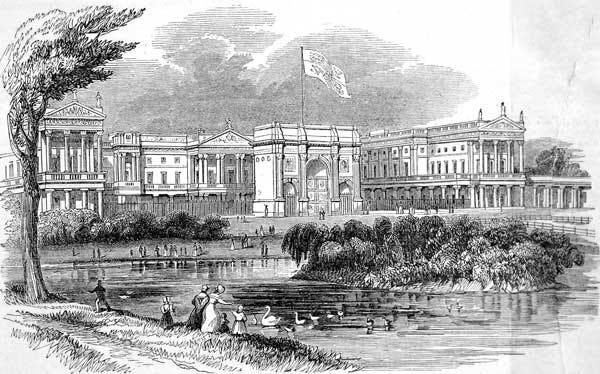

The arch was designed by John Nash in 1825 as a quintessentially neoclassical celebration of Britain’s triumph over Napoleonic France a decade prior. However, Nash’s original plan (of which a model survives) was far more ambitious than the arch which exists in the image above and today. Its splendour was to outshine the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel in Paris and the Arch of Constantine in Rome. Trafalgar and Waterloo, Nelson and Wellington — this was to be a monument of undiluted glory dedicated to two military heroes of the United Kingdom. The pedestal atop the arch alone would have featured:

Britannia, flanked by a lion and a unicorn, displaying a medallion of Nelson.

A medallion of Wellington, held up by personifications of Europe and Asia seated on a horse and a camel respectively.

Four statues of Victory (of Greco-Roman inspiration), one on each corner.

A bronze equestrian statue of George IV (the reigning monarch at the time Marble Arch was first designed and Prince Regent during the Battle of Waterloo) at its summit.

Readers may reasonably consider these features excessive, yet they doubtlessly embodied the strength and power Britain wished to project about itself at that point of hard-won military victory. Another concept Marble Arch quite obviously signified was the ostentatiousness of George IV, hence plans were drastically scaled back when he died in 1830 and William IV disapproved of the expense required to finish executing Nash’s plan. Nash was sacked and replaced with Edward Blore, leading to the completion of a more subdued arch in 1833.

The arch we have today is nonetheless a brilliant piece of architecture, certainly doing well without the relentless militarism of Nash’s original design. The panels of the arch are a number of personifications in Greco-Roman style of worthy national ideals (for example, one depicts figures of Virtue and Valour), as well as the union of the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland. This achieves similar effects to the original plans, namely tangible representations of national pride and strength as a reiteration of civilisational willpower. Likewise, the beauty of the monument is a statement of faith in the personified ideals it displays.

But what of the unused sculptures from the original design? Instead of them disappearing forever or being destroyed, Blore had them spread about the other architectural projects of his time. Many of the battles which would have been depicted on the arch were instead built into the central courtyard of Buckingham Palace as part of its renovations. The statue of George IV found its way to a plinth in Trafalgar Square. Europe, Asia, Britannia and the statues of Victory were modified and used by fellow architect William Wilkins in the construction of the National Gallery. Note the energy of this iteration of British society compared to the present, in this case its ability to construct multiple iconic national landmarks nearly simultaneously; we can barely build an artificial mound. After Wilkins took his share, the remainder sadly did disappear into obscurity. However, these might not be lost after all. A panel of the Battle of Cape St. Vincent, from the originally planned section on Admiral Nelson’s life, reappeared in Regent’s Place in 1996.

Why was this possible? Put simply, the unused sculptures were imbued with a passion and confidence that made them compatible with other landmarks. All the buildings mentioned and their sculptures were artefacts of a civilisation happy to celebrate its achievements. The beauty of the sculptures uplifted places which were themselves built beautifully to start with. The present cultural paradigm generally engages in the opposite, but manifestations of beauty will always be important in conserving the gains of civilisation. For those engaged to such ends, to destroy or forget presently unused art is to surrender to the rampant forces of entropy. Therefore, one should heed the history of Marble Arch as evidence that traditional high art will always have a place in the world.

Sources

Note: I struggled to find primary or authoritative secondary material readily available online about the early history of Marble Arch, so perhaps take these with a pinch of salt.

Historic England Research Records on Marble Arch

The Story of Marble Arch (There are a couple of seemingly reliable literary acknowledgements at the end of the webpage.)