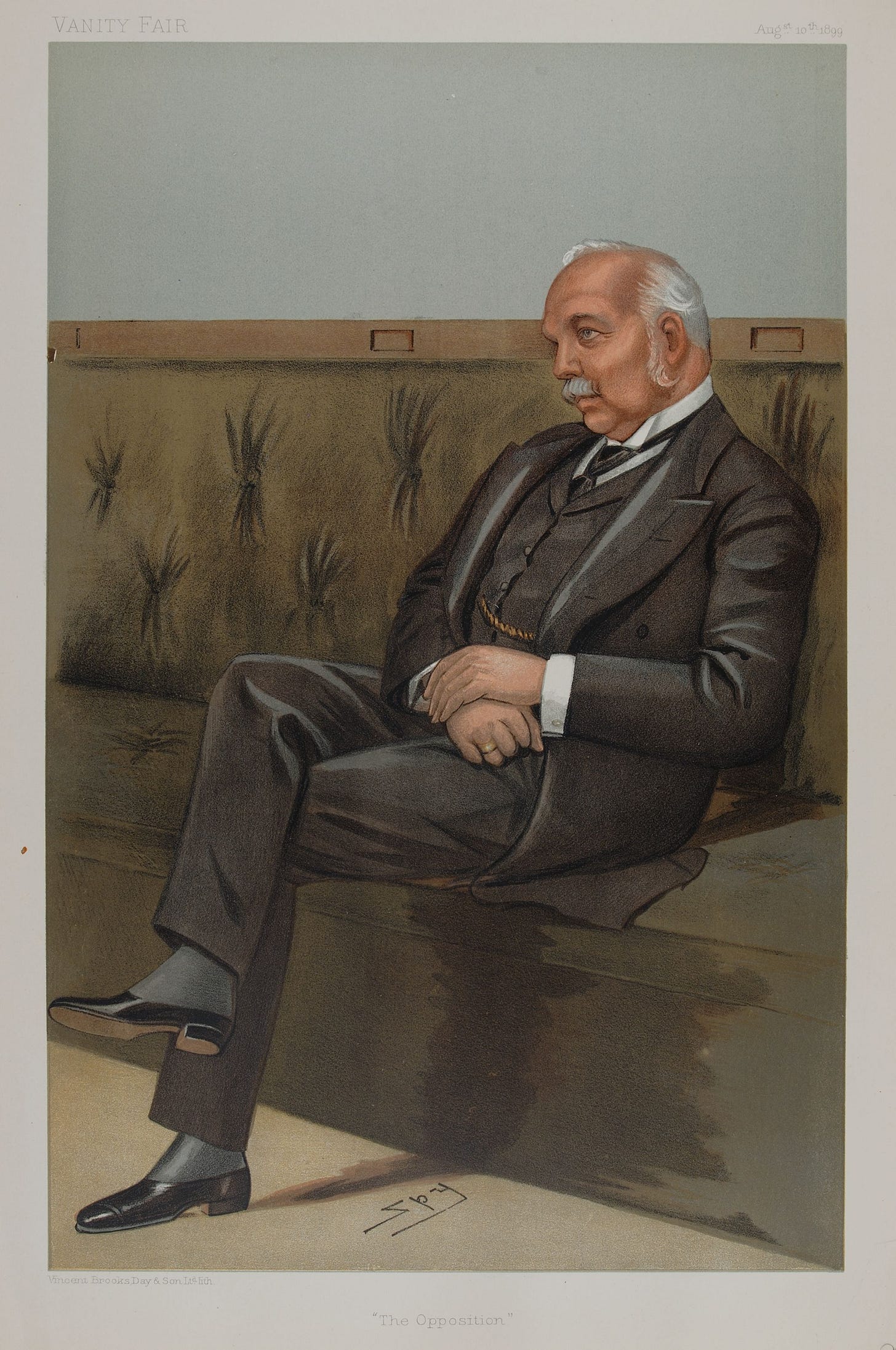

Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman is one of the lesser-known Prime Ministers of the twentieth century, often overlooked in favour of his successor Herbert Henry Asquith. If Asquith had his way, however, Campbell-Bannerman might never have become PM at all. The Relugas Compact plot of late 1905 was a classic of Edwardian political intrigue, as well as epitomising the period’s factiousness, yet managed to fall completely flat almost as soon as it had an opportunity to change the course of politics.

The emergence of the plot centred on the difference in foreign policy outlooks between Campbell-Bannerman and Asquith. The former was solidly part of the late Gladstonian tradition, the combination of William Gladstone’s final premiership of 1892-94 with the 1891 Newcastle Programme of the Liberal Party’s Radical faction. This doctrine opposed aggressive ventures for the sake of national aggrandisement, but possessed a strong guiding moral dimension from Gladstone himself that could produce equally complicated and bloody outcomes. On the other hand, Asquith was a prominent Liberal Imperialist, whose leader Archibald Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery, succeeded Gladstone in the brief ministry of 1894-95. Their beliefs were more self-explanatory, taking what they viewed as the more patriotic stance on imperial conflicts, as well as downplaying the importance or urgency of Irish Home Rule within Liberal policy. The two schools of thought came into increasing conflict with one another as the Second Boer War (1899-1902) progressed. In 1901 alone, Campbell-Bannerman repeatedly denounced the “methods of barbarism” used by the imperialist Unionist government against the Boers, whereas Rosebery called for a “clean state” of policies in an implicit rejection of the Newcastle Programme. In February 1902, Rosebery formed the Liberal League with Asquith and fellow future plotters Richard Burdon Haldane and Sir Edward Grey, 3rd Baronet, as an open challenge to Campbell-Bannerman’s leadership. However, they lost any political momentum with the end of the Boer War in May and had only succeeded in isolating themselves from most of the Liberal Party. In the following months, Liberals of all types rallied around free trade and opposition to the Education Act 1902, minimising the differences between any putative factions.

Therefore, once the fall of the Unionist government became likely, the Liberal Imperialists were not approaching power from a position of strength. Rosebery, whom they still saw as their leader, slumped back into his characteristic detachment from party politics and unwillingness to hold high office, both of which had marked his brief premiership a decade prior. Nevertheless, they still distrusted Campbell-Bannerman’s potential foreign policy. In September 1905, Asquith, Grey and Haldane met at Grey’s fishing lodge in the village of Relugas, Morayshire, where they concocted a plan to guarantee their influence over a Liberal government. The three politicians would refuse to take office, attempting to leverage their sway over a section of the Liberals and Asquith’s seniority as a former Home Secretary, unless Campbell-Bannerman took a peerage, Asquith became Leader of the Commons, Grey Foreign Secretary and Haldane Lord Chancellor. They believed this would give them sufficient influence over both the Commons and foreign policy whilst neutering Campbell-Bannerman’s control as Prime Minister. It seemed the plotters had resigned themselves to Rosebery’s withdrawal from politics and it appears he was never informed of the compact.

The Relugas Compact was not entirely founded on the self-interested pursuit of power, although that clearly remained its defining element. Campbell-Bannerman and his wife were both ailing, which gave him some doubts about his ability to bear the strenuous duties of Prime Minister. These concerns had been relayed to Asquith by Herbert Gladstone, the Liberals’ Chief Whip and youngest son of the distinguished former leader. However, once the Unionist government finally resigned in December 1905, the plot collapsed almost immediately from Asquith accepting the offer of Chancellor without preconditions. When Grey and Haldane then refused office as planned, the attempt was already bungled and Campbell-Bannerman’s resolve was strengthened. Grey had actually been offered the position he sought, Foreign Secretary, but delayed the formation of the new government by refusing to serve with Asquith in a different role to those agreed at Relugas. This was an obviously nonsensical stand, so Grey was eventually persuaded to join the government; Haldane became War Secretary.

By its own terms, then, the plot was an almost complete failure. Campbell-Bannerman remained in the Commons throughout his premiership, redoubled in authority by the landslide election victory for his party in January 1906, whilst only Grey was in the intended position. Despite that, all three received powerful offices and Asquith was heir-apparent to the leadership. The latter had been the case since Campbell-Bannerman became Liberal leader in 1899. Moreover, Liberal Imperialism had long lost the significance and distinctiveness it enjoyed during the Boer War, as the domestic social reforms of New Liberalism became the universal agenda of the party. If factions mattered by the end of 1905, Campbell-Bannerman had successfully bound the Liberal Imperialists to his leadership over Rosebery’s, even though the appointments of Grey and Haldane arguably constituted a compromise to secure unassailable party unity. When Asquith succeeded Campbell-Bannerman upon the final collapse of his health in 1908, it was an entirely amicable transition founded on the former’s loyalty to his premiership; New Liberalism continued unchanged as Liberal policy.

The Relugas Compact ultimately represents the passing flights of fancy always encouraged aplenty by the relative powerlessness of opposition, but which ought to be disposed upon entry into government. Albeit with momentary reluctance, this brief resurgence of earlier factional disputes was rightly subordinated to the sober objects of governing. This does not preclude tensions or splits emerging whilst in government, as eventually occurred between Asquith and David Lloyd George during the First World War. Yet the potential irresolution of such issues prior to government, even their indulgence with the acquisition of political power, should not attract much sympathy from onlookers, either in historical contexts or today.

Bibliographical Notes

For the rivalry between Campbell-Bannerman and the Liberal Imperialists, see: Bernstein, George L. “Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman and the Liberal Imperialists.” Journal of British Studies 23, no. 1 (1983): 105-24.

For more on the relationship between Campbell-Bannerman and Asquith, as well as an account of the compact, see: Sharpe, Iain. “Campbell-Bannerman and Asquith: An Uneasy Political Partnership.” Journal of Liberal History 61 (2008): 12-19.