The Prospect of Sentimental Conservatism

What will become of conservatism in a Britain without the Conservative Party?

As the current election campaign in Britain drags on, we now find ourselves startlingly close to the total destruction of the Conservative Party as an effective political force. The possibility is certainly greater today than it was in 1997 or 1906, and for good reason. Piles of commentary pages already exist, including from this writer on occasion, to describe how the party leadership has utterly squandered their fourteen years in power and spurned their eponymous ideology. Plenty more will surely be written in the coming weeks to exhaustively dissect the political history steadily unfolding before the country. In electoral terms, Reform is marketing itself as the Conservatives’ replacement, especially since the return of Nigel Farage to a position of active leadership, which has a fair chance of success before the end of the decade. If it shall follow the playbook of its 1990s Canadian namesake, a merger between the parties could be pursued wherein the shattered Conservatives would have little unique to give besides their name and organisational infrastructure.

Despite all the triumphalism about the Conservatives imminently being taught a lesson for their missteps and their removal as a block to genuine conservative politics, the eventuality of Reform’s dominance over the centre-right introduces a huge problem which seemingly very few have realised. Simply put, Reform is an openly populist party, not a conservative one. At best, it is re-treading tired neoliberalism and populist. Any branding exercise or spin it could deploy in the future, including a rename from taking over the current Conservatives, would not change the fact it is fundamentally detached from the conservative tradition. Its desire to dispose of the House of Lords and the Westminster voting system are on the same level of constitutional destruction as Labour’s propositions. Farage wants schoolchildren to be better taught about history, but this instinctive response to the growing trend of national self-loathing will be challenging for Reform to properly articulate and remedy from its rootless position, one solely a reaction to the existing duopoly’s shortcomings.

British conservatism, without its natural party willing to sponsor it, said party facing extinction anyway and Reform unwilling to inherit its abeyant mantle, has no significant bastion left to retreat to as an active and living tradition. The ultimate bureaucratisation of institutions has left them unfriendly to any approaches, whilst the Church of England is likewise a quasi-secularising shell of its former self. Yet conservatism is more than a political ideology, for which mourning might be a debatable affair. Conservatism is a philosophy, a way of seeing the world permeating many disciplines to positive effect, which has become a cornerstone of Western thought. However, its worldly fortunes are closely tied to the extent of its political application to reify its thoughts, thus conservatism is struggling for survival. Although it would be ideal in the present situation to separate the political aspects from the rest, disclaiming the thread of thinkers from Burke to Scruton would condemn the aesthetics and philosophy just as much.

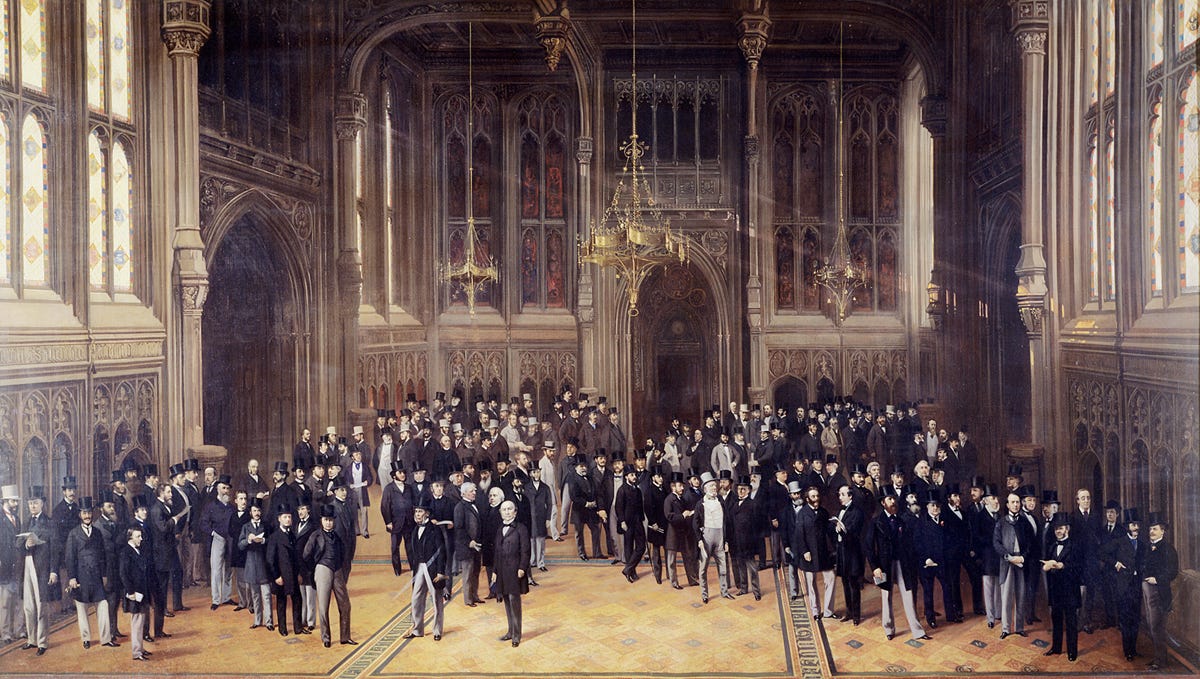

The Conservative Party might not be the first party to be destroyed in British political history, but it will likely sting the most due to how many informed participants exist in modern democratic politics. Since the Liberals managed to cling to life after their collapse in the early twentieth century, the potential disappearance of the Conservatives from the political landscape will be more reminiscent of their spiritual predecessors in the Tories. After the party died out in the 1760s, to become little more than an insult levied against certain Whigs for the subsequent six decades, certain identifiably Tory individuals like Samuel Johnson carried on as such regardless. He and others of his time, specifically the mid- to late eighteenth century, could reasonably be described as sentimental Tories, cultural holdovers without a political party to call home and receive their ideas. This only lasted one generation, effectively constricted by the human lifespan in the same manner as the party’s demise from their decades of proscription; Johnson died in 1784, only a few years before Edmund Burke’s ideas began to consolidate into something new.

Today, a similar phenomenon of sentimental conservatism has already emerged and easily amongst larger numbers because of the Conservatives’ abandonment of their ideology years ago, as well as the electorate’s greater access to information and the realities of contemporary politics. Peter Hitchens became the first of these around the turn of the millennium and still acts as its informal figurehead, whilst Roger Scruton’s elegiac tomes conformed to type but never truly gave up on the party. There are many others with unrewarded residual faith in the party who will swell these ranks soon enough. It should also be stressed that the nature of the holdover is much greater, essentially constituting the lion’s share of the nation’s remaining cultural and historical continuity. Nevertheless, not all those who might see themselves as sentimental conservatives could muster any personal understanding of, for instance, the hereditary House of Lords or the functions of historical continuity once routinely performed by local government. Most of the political system and its manifold orbiters cry for reform or abolition, elsewise silent indifference or active misconstruing whilst others do such work, at the scantest sight of this crumbling inheritance. It increasingly seems as if history or culture, of any meaningful depth and grounding in truth, must be observed only by candlelight, lest vandals or connivers to either side of conservatism take notice and attempt to obliterate something else.

Is there any hope for conservatism, then? Not yet, at least in electoral terms. There might be some consolation in that the potential paths for its maintenance could still be made to exist, akin to conservatism’s sprawling nature, beyond the fate of one political party. However, for the reasons discussed, it must either continue wholesale or wither into isolated remnants to be later forgotten. For all its flaws, as all sets of ideas have their imperfections, it does not deserve the latter fate. As long as there are living practitioners, the grand intellectual tradition can survive and possibly regain its rightful prominence. Even without a direct political home, it has so much to say through time about the world today if some remain willing to transmit its plethora of observations. If it falls victim to the follies around it, out of sheer apathy and resigned attitudes about politics, the country will be much worse off for having destroyed perhaps its best guide to the tumult of the present.