About a hundred years ago, there was a general election. The October 1924 election was not the most remarkable event in British political history: the Conservatives won a landslide primarily at the declining Liberals’ expense, arguably as an anti-socialist reaction to the first Labour government formed at the start of that year. The fourth-largest party, though, following the Conservatives (and associated Unionists), Labour and the Liberal Party, was more unique. This was the twelve candidates standing under the Constitutionalist label, technically an independent grouping rather than a bona fide party. Seven were elected, including their leader Winston Churchill, on a simple yet prescient platform which perhaps merits revival in a contemporary politics that could soon face a number of revolutionary constitutional changes.

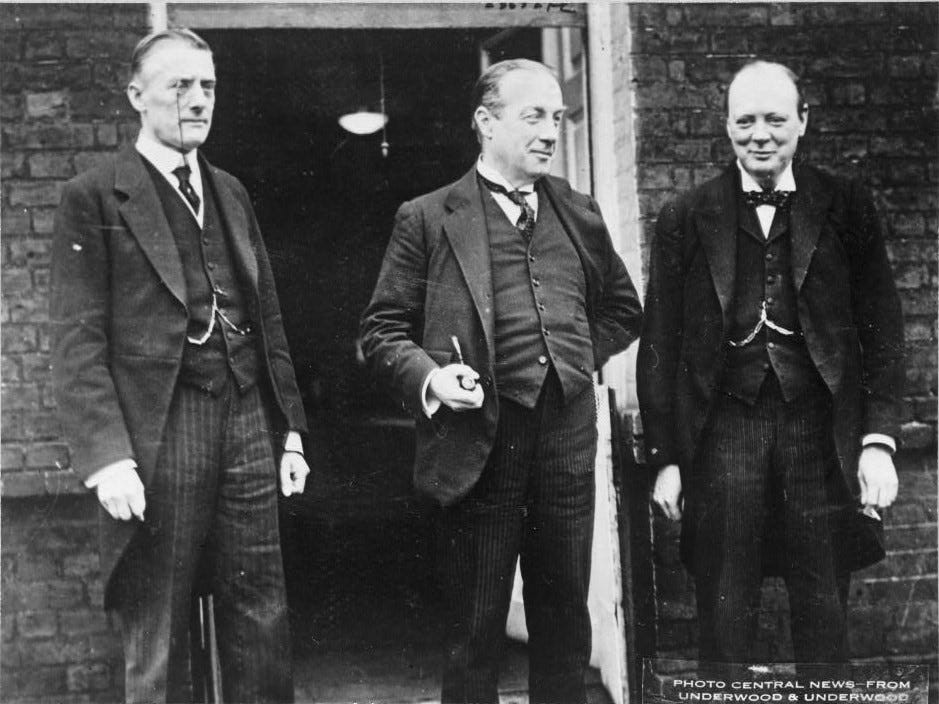

Simply, Constitutionalist candidates used their label to signal their commitment to British constitutional government and its underlying principles. By 1924, the constitution had just experienced a major bout of reforms, including the Parliament Act 1911 and Representation of the People Act 1918, but its broad historical continuities and laudable principles were faithfully maintained; the later Representation of the People Act 1928, which brought about equal universal suffrage between men and women, reinforced this trend. However, the prospect at the time of a socialist Labour government, one stronger than their incapable ten-month minority administration, threatened sustained radical change. Constitutionalists thought, perhaps rightly given their already longstanding promise to abolish the House of Lords, that a Labour majority would not have fully abided by customary principles and the constitution’s organic nature. It should be noted the Liberals and Unionists were themselves anti-socialist and mostly in favour of the constitutional status quo that had settled by the early 1920s. Notwithstanding, the Constitutionalists emerged as a distinct grouping from the two after David Lloyd George’s National Liberals, previously in a somewhat anti-socialist coalition with the Conservatives, re-joined Herbert Henry Asquith’s Liberal Party in 1923. The non-partisan label hence gained support where local Unionist and Liberal associations agreed to continue cooperating but candidates chose to run under neither name. Although Churchill sought to establish a formal Constitutionalist Party, the election came too soon to create anything permanent. Thusly, the Constitutionalists dissolved after the election, almost as soon as they had emerged. Of the seven Constitutionalist MPs, four retook the Liberal whip whilst three joined the Conservatives. For Churchill, it was a case of re-joining the Unionists after twenty years as a Liberal defector, whereupon he was appointed Chancellor by the victorious Conservative leader Stanley Baldwin.

Arguably, the Constitutionalists would have struggled to carve out a sustainable base of support from the parties which absorbed them. Yet, their fundamental message was at least a little prophetic, forecasting the needlessly drastic changes and outright constitutional vandalism of subsequent Labour governments, most notably the reign of New Labour. As for the present, the possibility of the traditional constitution’s final disintegration looms larger by the day, but the Conservatives’ indifference or token opposition is about the best that can be expected of all the modern parties. This is obviously insufficient. Constitutionalism, not necessarily as a party but as an idea, is needed more than ever to vigorously oppose the impending experiments in federalism, ‘modernisation’, House of Lords abolition, proportional representation and further domineering bureaucratisation which may occur under the new Labour government. Moreover, a more substantial knowledge and understanding of the constitution, especially before Blairism, could be derived from a renewed constitutionalism to demonstrate that the options for reform are manifold. After all, not everyone in the past was a fool, whilst some proved particularly adept at governing Britain using those venerable practices and institutions now unquestioningly dismissed. Indeed, it was under the same archaic constitution as the Constitutionalists defended that a free and representative democracy had been realised without the need for revolution or otherwise jettisoning the pre-existing state apparatus, a strikingly rare achievement in history.

Although faith in the more rooted constitution of yesteryear may seem a naturally conservative position, despite that the median Constitutionalist was more or less in the centre, the maintenance of stable, accountable, effective and deliberative government through responsible change and administration should be universally held aspirations. The Blairite constitutional revolution, as well as its custodianship under recent Conservative governments, has not produced these outcomes. Accelerating the prevailing constitutional trend, as Labour intends, does not hold much promise of altering any existing trajectories. In the absence of much prospective respect from Labour for constitutional continuities, one could do worse than learning from or reimagining constitutionalism in its extolling of the sound principles of a still tangible and meaningful inheritance.